Che chiedi mai, tu, ignoto spettatore dal cuore sensibile, al teatro muto, ma pure parlante, un misterioso linguaggio ai tuoi occhi mortali e alle tue fibre vibranti? Che domandi tu, mai, spettatore dalla fantasia sempre ansiosa, sempre anelante, sempre sognante visione incomparabile, al bianco schermo che è la tua croce e la tua delizia? Che vuoi tu, mai, spettatore dalle sottili curiosità intellettuali, dalla mente indagatrice delle grandi figure antiche e dei grandi fatti storici, che il tacito palcoscenico ti mostri e ti descriva? Ognuno di voi tre, spettatori multiformi, spettatori multanimi, ma, infine, serrati in queste tre grandi categorie, domanda una impressione, una sensazione differente! Chi vuol esser commosso sino al lieto sorriso, sino alle lacrime; chi vuol esser lanciato in un vasto sogno, in un sogno senza confine; e chi vuole imparare, conoscere, apprendere e di giudicare, con la sua ragione e col suo criterio… Ebbene, Intolerance, la maestosa, la imponente, la insuperata pellicola che viene d’oltre terra e d’oltremare, la pellicola che la magnifica produttrice, l’America del Nord, manda a noi, manda a voi, spettatori dal triplice desiderio, la pellicola che Griffith, il poeta metteur en scène americano, ha creato e lanciato all’ammirazione del mondo intero, Intolerance è fatta per sorprendere ed esaltare ogni spettatore, nel suo intimo bisogno di conoscenza, di sogno, di emozione!

Matilde Serao, Napoli Ottobre 1917

Convien ricordare che, oggi, l’uso dell’aggettivo “colossale” va diventando oltremodo antipatico e sospetto.

Esso, più che ogni altro, ci sarebbe sembrato spontaneo e preciso per definire la somma di sensazioni che s’affollano tumultuanti al nostro spirito dopo una prima visione di Intolerance.

I critici dei maggiori quotidiani europei e d’oltremare, sebbene adusati a giudicare più complesse e grandiose opere d’arte, battono invano la campagna, ricercando affannosamente, tra le sterili aiuole della fantasia, i fiori enfatici del panegirico per costellarne la loro prosa in onore di Intolerance.

Infatti, ogni tentativo di critica deve ritenersi ozioso e disutile. Intolerance, come i grandi capolavori, sfugge ad una disanima pettegola e minuziosa. La sontuosa magnificenza delle sue linee, la vastità del suo contenuto morale, la perfezione ineguagliabile dell’esecuzione provocano in noi piuttosto un senso di stupore e di orgasmo estetico, tale da paralizzare i nostri poteri critici, incitandoli soltanto ad un’ammirazione ingenua ed incondizionata.

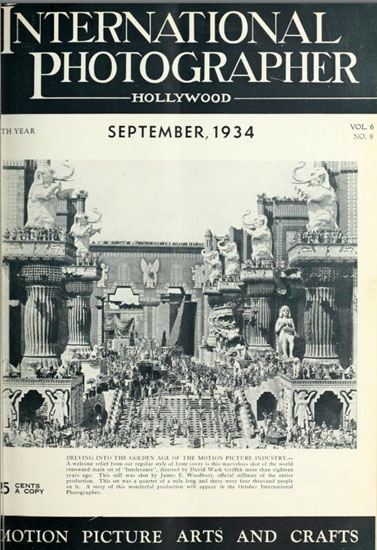

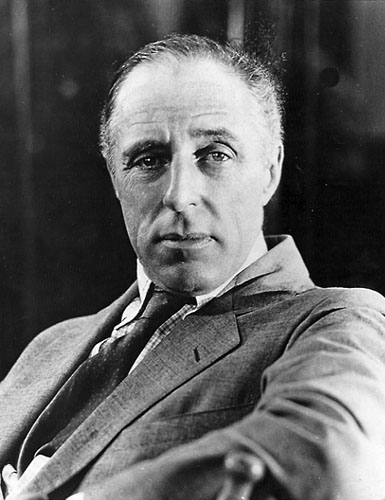

D. W. Griffith, che ha pensato e diretto le scene di Intolerance, può considerarsi un innovatore. Questo giovane americano, sconosciuto fino a pochi anni fa, trova dentro di sé tutte le audaci energie della sua razza e, d’un balzo, si mette all’avanguardia della cinematografia con una film, Intolerance, che è costata sei milioni di dollari, vale a dire circa trenta milioni di nostra moneta, facendovi muovere poco meno di settantamila attori, ricostruendo con fedeltà storica e coscienza d’artista i fastigiosi palagi e le turrite castella di civiltà remote, rievocando, innanzi al nostro spirito commosso, i grandi fatti storici, l’avvento del Messia nel suo divino epicedio, le gesta dei condottieri insigni, le costumanze di popoli dispersi, le battaglie, gli odii, gli amori, strappando alla Bibbia e alla Storia pagine inobliabili, documenti immortali dei tragici fatti dell’umanità, ricollegando questi con un tenue nastro ideologico e fantastico alla tesi che, soverchiandolo, incombeva sul suo intelletto di artefice ispirato e temerario.

(…)

Il soggetto di Intolerance non va narrato.

Si è già troppo deplorato l’abitudine dei critici dei quotidiani che s’abbattono sull’ultima commedia, ne rabberciano il contenuto ed offrono sollecitamente ai loro lettori una favoletta insipida, sempliciotta, irriconoscibile dallo stesso autore.

Chi, ad ogni costo, si accingesse alla dura fatica di raccontare quello che si vede nei tre lunghissimi atti d’Intolerance, compirebbe un ingrato fuor d’opera, tanto più inutile in quanto che allo spettatore, che esce dalla sala di proiezione, non occorre rileggere cosa che già sa di propria scienza.

(

Silvino Mezza

Immagine e testi dalla brochure italiana del film: Teatro-Film D. Cazzulino, Torino 1917 (Archivio In Penombra).