The Black Lotus Flower of Europa has been transplanted to America… but…

A shriek rent the air. It was the climax.

The torment of music ceased, and Pola Negri a quivering, throbbing, brooding black mound of nerves lay huddled together upon the floor in front of the gilt doorway.

Slowly, almost tenderly, to an accompaniment of plaintive melody, a half-naked Nubian slave bent over her, touched her and then, with the semblance of a deep sorrow etching his face, lifted her to her feet. As he wound about her the lace of a mantilla, she stood swaying a moment, her eyes listless—empty their wells of feeling, her head beating back and forth in a dull rhythm. Then, step by step, hesitatingly, uncertainly, she half tottered out beyond the range of lights, beyond the camera itself, lost seemingly in a hypnotic mood that overhung scene and setting and onlookers, a mood nocturnal and vast as the surging, passionate desert blast that had swept and wasted and finally was destroying the bloom of its exquisitely deceptive flower— Bella Donna.

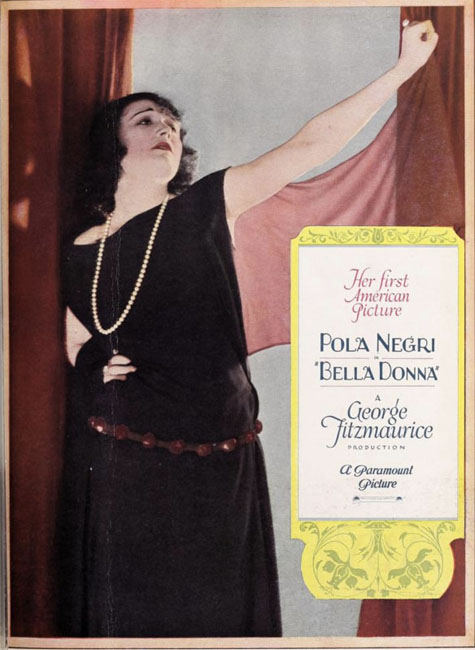

I had been watching one of the final scenes in Miss Negri’s first American picture. Nobody but would have admitted this a privilege. It was, in fact, almost lese majesty for any stranger to be on the set. Nearly as many permissions had to be obtained to enable me to look on as are required for an audience with a Grand Lama. At least, I was told that they had been obtained, but the possible significance of this excess of formalities was absolutely lost on me once I came aboard Baroudi’s love barge, where it was securely moored to the floor of the studio stage. I am not particularly concerned with formalities, anyhow, not even when they concern Europe’s most celebrated screen actress.

Baroudi’s love barge was the background for the culminating emotional scenes of Pola Negri in “Bella Donna.” The hysterical episode I had just observed, with, I might say, almost bated breath, was one of these. The heroine had just received her blunt congé from the sheikish Oriental exquisite, who had ensnared her. She was left quite alone in a world that did not love her and did not want her. The dark lotus of her charm was broken, the leaping flame of her youth was dying away. Destiny’s tragic claim was written on her brow, and one sensed for her the approach of the blackest hour:

Less than the dust beneath thy chariot wheel,

Less than the rust that never stained thy sword,

Less than the trust thou hast in me, my lord,

Even less am I, even less am I

Truly, I believe, you have never yet really seen Pola Negri on the screen. Always there has been some obscuring fault of make-up. Even as it has actually clouded her resplendent beauty, so, too, I feel, it has but half disclosed her radiant art.

To behold her now, fully illumined by the dazzle of our insurpassable lighting, and the minute excellence of our photography, will be like a glorious revelation. Lily-white her hands and face, orchidlike the spirit of her beauty. She is at once the sinister nightshade, and the white lotus, a blossom of ecstasy and a bloom of torment

A dark cool night, and oversweet

With tuberose breath;

A jeweled javelin in the heart,

Ecstatic death.

Those who have appeared in her picture have confessed to me their absolute inability to cope with her. They accuse her, in fact, of not giving a single thing. She rules the set absolutely as its mistress, and that is something that can well be understood after one watches her and realizes how much of herself she literally hurls into her acting.

She has been known to stand for minutes before a mirror, pretending to be making up her lips or her eyes. In reality she was not making up at all. That was only a pretext. She was going through her preparations for the next episode. She tested every expression of her face, studied it from every angle, endeavored to get over some undreamed-of nuance of feeling, some absolutely new light of eyes, curve of lips, engraving of forehead, to eliminate if possible a spoken title, which titles, she frankly admits, and with a positive venom in her voice, “I hat’.”

To Pola Negri music is the essence of her art. One might almost say that it is also the essence of her being. To it may be ascribed the vivid fluency of her acting. In Europe she was accustomed to have only the finest sort of compositions to accompany her acting — Tschaikowsky, Beethoven, and sometimes—though rarely, because he depresses her—Wagner. On her arrival in Hollywood she cast out all the jazz ensembles that were brought her as if they had been the seven devils. It was only after many fits of temperament and finally an absolute refusal to work, I believe, that she finally obtained a makeshift of piano and cello that pleased her. A feverish Lament of Grieg had been selected as the motif for her closing emotional tempest in “Bella Donna.” The melody tossed and undulated beneath the bow of a cellist, becoming every moment more languishing, more restless. As Pola faced Baroudi, and learned that, after her bitter sacrifice of Nigel, the Oriental no longer wanted her, that, in fact, a new Circe had already captivated him, the elegy in tone became a veritable delirium. One sensed almost a demand from the actress that the music should be her stimulus; one felt that the players played for her as they had never played before. Such, indeed, is the magnetism the well-nigh uncanny bewitchment of Pola.

Strangely, fantastically, in tune with her desespoir, the while, was the love boat’s Nirvana harmony in black and gold—a subtle Oriental harmony built on one of those weird scales of tone that come out of the heart of the Far East. The deep inlays and intricate patternings of the narrow doors became momentarily deeper and darker. The grilled windows, fretted with a design as dainty as Chantilly lace, were lost in the febrile mists. The deep divan cushioned with inky and yellow silks, became wan as in the light of dawn, its fitful purple scarflike coverings softening to amber, and its rose and fuchsia hangings to a methitic mauve. One sensed, too, almost the sick lapping of the waters of the Nile, and the oppressive portents of pyramids and sphinx and desert waste.

I know of no other setting that more admirably. seemed to accommodate itself to the moods of its star, even as it also breathed so much of the storied wonders of the incensed far away. The skill of George Fitzmaurice, the director, who promises to become truly recognized as an artist of the screen, I sensed, had been at work again, and this time for the sake of a locale that had stimulated all his fancy for the exotic, even as “To Have and To Hold” had caught his imagination in the web of the romantic.

The story of “Bella Donna” has, of course, been modified. A reason has been given for the heroine’s malefic character. Ouida Bergere, the scenarioist, told me that she felt this was justified because the original Bella Donna of the Hichens novel, while she was sirenically alluring as colored with literary descriptions, would not produce the same illusion of enchantment when coldly lighted in the silver shadows. Also, I have no doubt, Bella Donna, thus portrayed, would be far too pathological a specimen for the sensitive dispositions of the censors, and rather than risk her mutilation, it was decided to temper her. This was accomplished by allowing her to suffer an unhappy marriage before the main story opens. We sense Swansonian wormwood here, but what of it? Pola herself approved, for to me she repeated her oft- heard assertion that she docs not “want to play ze bad ladies.”

What she really means by this is that she does not want to play rôles without sympathy—straight vampire roles, sans raison d’être. She wants to reach the heart of her public as well as its mind. Will she? I wonder. Pola and the public’s tears? Somehow they seem incompatible. Yet it is for those tears that she seeks and strives and struggles with the frenetic intensity of her art, showering in diamonded cascade the scene with her own unleashed grief.

“When I weep it is not for myself alone ; it ees for everybody,” she told me, half chanting the words. “I theenk always of audience, people, everywhere, all, sorrowful weeping wiz me. I poot my whol’ heart, my whol’ soul into my art, my expression, my tears, so zat zey may feel wiz me what I feel, so zat zey perhaps suffair what I suffair.

“I want to play Bella Donna sympathetique. I do not believ’ she should be play’ like bad woman—like vampir’—I do not believe that woman ar’ evair vampir’ by natur’. Woman become vampir’ because of situation, circumstance—what you call—fate! No woman become bad by natur’, but by fate.”

“And because.” I ventured, perhaps…because, of some man? I mean that woman’s wrongdoing is contingent—dependent sometimes on the wrongdoing of some man.”

There was a subtle flash between us. And then, a moment’s pause, and

“That is an interesting psychological question, but”—and this was delicately yet, I might say, nearly tigerishly emphatic—‘“I do not care to discus’…!”

There was finality in the answer. Our talk ended shortly after. It taught me that Pola is not given to gossiping about the questions of life as we in America do quite casually and on every street corner. Her experience with telltale interviewers has, perhaps, made her more cautious than ever! Anyway, she cares only to converse regarding her art, and life only as it is related to her art. To all queries aside from this she generally replies now, “I do not care to discus’ ’’—even as, to the inquiries concerning her rumored marriage to Chaplin, she has maintained a frigidly dynamic silence. You can guess, if you will, what her views and her sentiments are regarding life and its personal relationships, but you can only know her through her art. There is about her consequently something enigmatically alluring, and that, I believe, is her highest enthrallment, that and her marvelous treasure of talent and emotion.

Will America change her? One wonders, because one can only wonder. She may remain here for the space of two years now, and in that time what may not happen! America has always been reckoned a great melting pot for all. Yes, perhaps. For nearly all, but there are some… like Pola.

Edwin Schallert

(Picture-Play Magazine, March 1923)