It is a doubtful point whether it is greater to make history or to re-make it; whether the strong man who bends the years under his hand is mightier than he who, with magician’s touch, raises them from the dead and causes them to live again. At any rate, there can be no question that the reconstruction of the past is one of the greatest triumphs of which man is capable, for to repair the ravages of Time is to open the gates of our own limited age and allow us to enter again into the lives and thoughts and emotions of those long since departed.

Of all attempts at reconstructing history there is little doubt that the cinematographer’s is the most successful hitherto known. Into his magic mirror this modern Cagliostro can summon at will the ghosts of vanished centuries, breathe into them the colour of life, and cause them to move at will by power of his enchantment. It is like looking through a window into the past. One lives now; but one sees then.

Coming to the subject of this little article, we have never seen a more wonderful historical picture than this remarkable film of the Cines Company. It is not merely a portrayal of a single age, but a complete flight through time. We seem to be seated in some witch’s den; a mystical disc of light appears some writing flickers on the wall; and then, as though the world is giving way before us, we are thrown backwards into the earliest ages known to man. An ancient fane rises like a cool, grey shadow, and is peopled with warriors curiously attired. The pageant passes, and we are swept to the Abbey of our own great city as it existed centuries ago. There we are present at the inauguration of a custom which lives still, and but yesterday was celebrated. So are we led through the years, living again in as many minutes the events of a dozen centuries.

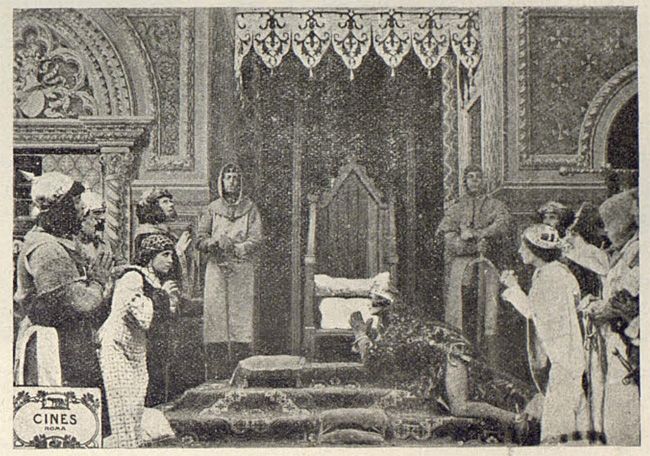

As the title of the film and our remarks will have indicated, this picture deals with the history of the ancient stone of Scone, which is now Westminster Abbey, set in the Coronation Chair. Although it is named the Scone Stone, however, its story dates back for hundreds of years before the Scottish church was even founded. The first scene is in the land of the Israelites. We see Jacob, the patriarch, tired by the heat of the day lying down to rest. As a pillow, he takes a large boulder, upon which he lays his head. And this is the origination of the famous stone. A little later we see the stone, already regarded as sacred, being borne into Egypt by the Israelitish emigrants as a memorial of their land. Every detail of this event in Biblical history is faithfully portrayed, and the setting is so perfect that it becomes hard to believe the scene is merely a re-enactment and not a picture of the actual happening. The next voyage of the stone is to Spain, whither it is caried with the greatest circumstance by a Greek prince. In the year 700 b.c. the stone is taken to the top of a mountain by Semon Brech, who declares that it shall be used as a throne there-afterwards. In the year 850 a.p. King Kenneth of Scotland finds the stone amongst some booty taken in war, and he sets it in the nave of Scone Abbey.

In 1296, Edward I., of England, storms Scone Abbey, takes Jacob’s Stone to London, and has it mounted in a chair at Westminster, from which time to the present day it has been used as the throne of kings. This wonderful series of pageants terminates with a picture symbolical of the might of Britain, showing Britannia seated upon the throne with her colonial sons gathered around her.

There is little need for further remarks, but we should like to add a word with regard to the wonderful manner in which the atmosphere of each different scene has been preserved. In a sequence of living tableaux of this kind it is often difficult to create that distinction between the pictures which should exist. The Cines Company, however, have been signally successful in this respect, and every scene bears a complete and separate individuality.

Length. 946 ft. Released August 5th

(The Bioscope)