di Jean-Louis Barrault

Charlot non fa un gesto che non sia un simbolo; un esempio fra mille: in un film, non mi rammento quale, Charlot finisce di confessarsi: esce purificato, con le mani giunte, gli occhi al cielo… viene avanti… inciampa e cade! Ritorno alle leggi di gravità, conflitto fra la materia e lo spirito.

Un metafisico potrebbe dissertare a lungo sull’argomento; Charlot lo affronta e lo risolve nel modo più semplice e familiare del mondo.

Il gesto che fa esplodere il simbolo provoca il riso. Senza il valore simbolico del gesto, Charlot non sarebbe che un pagliaccio: invece è un genio.

Ma osservate come tutte le sue figurazioni rimangono vicine alla vita quotidiana: Charlot aspetta il tram nell’ora di punta del traffico. Tutte le persone si precipitano; lui resta solo sul marciapiede. Secondo tram: passa una vettura e gli impedisce di salire. Terzo tram: Charlot prende lo slancio; salta al di sopra delle teste, calpesta i crani, penetra per primo nel carrozzone. La folla lo segue. La macchina da presa indietreggia: si vede allora Charlot sospinto dall’ondata dei passeggeri. Arriva all’altro capo del carrozzone, e si trova proiettato sul marciapiede. Moralità: i primi saranno gli ultimi. Sembra una favola di La Fontaine; e come è semplice! Charlot non si stacca di un centimetro dal più umile territorio e serba sempre la sua profondità.

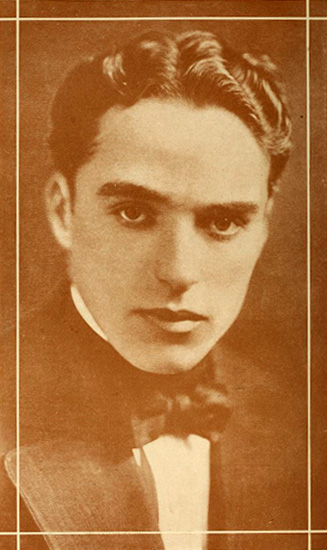

Ma quel che mi interessa di più non è tanto il creatore, il poeta moralista, quanto l’attore. Charlot ha trovato ciò che noi cerchiamo invano: ha trovato il suo personaggio. Questa difficile ricerca è il dramma proprio dell’attore. Ai suoi esordi, egli cerca la propria personalità; ne è preoccupato di continuo. « Questa parte non la sento. È contraria alla mia personalità ». Poi, quando crede di esser riuscito a stabilirla, cerca il modo si servirsene, vale a dire le parti che corrispondono alla sua natura. Quello che ci vuole è un personaggio. Come Molière ha creato il Misantropo, l’Avaro, personaggi che possono adattarsi a un gran numero di situazioni, così Charlot ha creato un personaggio che può adattarsi a parti multiple pur restando sé stesso, un personaggio astratto e vivo nel medesimo tempo. Per noi attori questo è il colmo della riuscita.

La facoltà di adattamento di questo personaggio è inaudita: e dipende dal fatto che la mimica di Charlot è basata su una tecnica straordinaria. La mimica di Charlot va dall’immobilità alla danza. Nel Dittatore, Charlot guarda bruciare la sua casa; è visto di schiena; non si muove affatto; e in questa schiena vi sono tutti gli elementi tragici di una lunga tirata. Chaplin raggiunge l’apice della musica che è l’immobilità.

Ma sa raggiungere anche la voluttà corporea, così che il suo giuoco partito da un certo realismo sbocca nella danza pura. Ricordate un’altra scena del Dittatore, quando Charlot riceve un colpo di padella sulla testa; egli compie lungo l’orlo del marciapiede una danza che sfido qualunque ballerino a eseguire.

Infine, senza volervi far penetrare nell’officina della mimica, vorrei farvi notare che tutti gli atteggiamenti di Charlot sono sintetizzati nel suo torso, che tutti i movimenti sono irradiati da questo centro verso tutte le altre parti del corpo contemporaneamente. Se Charlot fa l’ubriaco, non rappresenta un uomo con le gambe vacillanti, lui è ubriaco dalla testa ai piedi, è come un astro che gira.

E non strafà mai! In lui, il senso della brevità non viene mai meno. Dove chiunque altro gesticola due minuti, Charlot si esprime in quindici secondi.

Per noi attori, egli è un esempio di economia. Ci invita di continuo a rimanere fedeli all’essenza medesima dell’arte drammatica che è interpretazione, e ricreazione della vita attraverso il suo principale strumento: l’essere umano.

Ma la sua vera grandezza appare con evidenza a tutti: il più piccolo dei suoi gesti rivela interi un cuore e un pensiero infinitamente fraterni.

(Cinelandia, gennaio 1946)