Paris, Mai 1923

Nous demandions à la grande artiste qui va bientôt nous revenir avec « Maison de Poupée », version cinégraphique de la célèbre pièce d’Henrik Ibsen, quelle était sa recette de beauté et de bonheur. Voici ce qu’elle nous répondit:

« C’est le privilège de toute femme d’être belle, nous dit-on. Je prétends que c’est le devoir de toute femme! Mais ce devoir ne se résume pas au miroir, car la beauté est bien au-delà de l’épiderme…

« Vous vous rappelez la citation d’Addison: « Il doit plaire à Dieu lui-même de voir que ses créatures s’embellissent éternellement à ses yeux.» Mais qui nous dit qu’Addison ne voulait point parler de la beauté intellectuelle, ou de la beauté morale, ou de la beauté utilitaire?

« Que peut-on faire pour être belle? Pour notre beauté physique nous devons avec diligence observer l’abnégation dans notre vie quotidienne. Il faut se nourrir avec soin et intelligence et prendre de l’exercice régulier bien approprié. Pour la beauté intellectuelle et morale, il faut lire de bons et beaux livres et se mêler aux penseurs et aux travailleurs. Pour la beauté de notre âme, nous devons entendre de la bonne musique, vivre dans la compagnie des animaux et des oiseaux, aimer et respecter les petits enfants.

« En ce qui me concerne, je trouve mon plus grand bonheur — et quelle beauté vaudrait elle plus que le bonheur — en demeurant constamment active par l’esprit et le corps. Je me lève à sept heures et travaille jusqu’à sept heures et, si je n’ai pas à travailler la nuit, je me retire à neuf heures. Je m’efforce de remplir chaque jour ma pleine tâche, de lire beaucoup et bien, d’écrire un peu, de faire une heure ou deux de musique, des exercices en plein air —sans oublier un peu de temps pour les enfants et les bêtes favorites. »

Nazimova est arrivée aux Etats-Unis en 1904 avec une troupe russe, dont le principal acteur était Paul Orlener; elle joua d’abord dans un théâtre Yiddish de New-York.

Dés cette époque, comme le remarque spirituellement Herbert Howe, elle était spécialisée — même dans son propre pays — pour jouer les rôles d’étrangers. Aussi effective d’ailleurs dans la comédie que dans la tragédie.

Le Tout New-York alla curieusement voir, dans son faubourg, la brillante étrangère. Six mois après cette découverte, elle avait appris l’anglais — en prenant soin de conserver un léger accent — et abordait directement le public américain.

On dit qu’à cette époque Orlener et elle s’aimaient, mais que, prévoyant le brillant avenir qui attendait la jeune femme, il se sacrifia. Peut-être l’histoire a-t-elle été arrangée après coup…

Plus tard elle rencontra un acteur anglais, beau et imposant, qui fut son partenaire dans Trois Semaines. Elle l’avait déjà remarqué. Subjuguée par sa haute taille, son aspect dominateur, elle bondit sur une chaise et lui tendit la main.

Et ainsi Alla Nazimova devint Mrs. Charles Bryant.

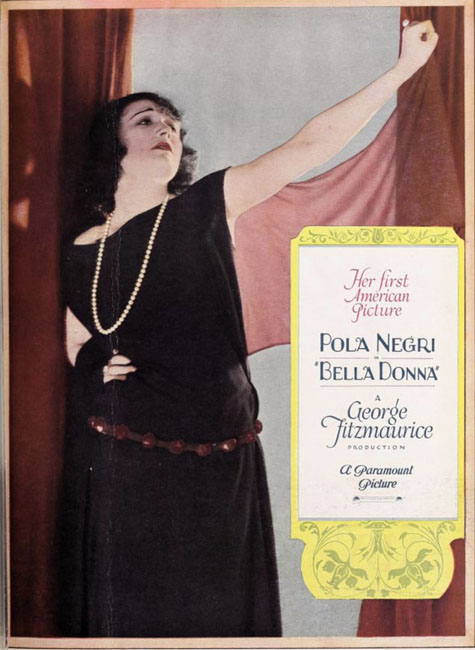

Le premier grand succès de Nazimova fut Hedda Gabler. Celui qu’elle obtint dans le personnage principal de Bella Dona (d’après le roman de Hichens), souleva quelque scandale.

Nazimova vit pour son art, nous assure Herbert Howe. Arrêtez son activité et elle mourra d’ennui faute d’autre intérêt. Son attitude défiante, parfois ironique, cache mal sa sensibilité. Elle est extrêmement susceptible en matière artistique: les critiques hostiles la touchent vivement, sans qu’elle veuille le laisser voir. Elle ne craint pas les responsabilités; la seule déclaration qu’elle n’est pas capable de réussir tel ou tel essai suffit pour qu’elle l’entreprenne. En dehors du théâtre, pourtant, aucune obstination. En affaires, aucune capacité; elle n’a pas mis d’argent de côté jusqu’à son mariage.

Nazimova habite, à Hollywood, sur la route qui mène aux collines de Beverley, une grande maison carrée, imposante, dont les murs sont teints couleur crème et qu’entoure un délicieux jardin, plus clos et plus intense que ne le sont d’ordinaire ceux de Hollywood.

Le salon est éclairé, le soir, par la lumière ambrée de lampes, voilées de gazes mauves et noires; de grands divans pourpres, des laques, miroir voilé d’une dentelle d’or lui donnent une personnalité étrange.

La poignée de main de Nazimova est franche, directe — masculine.

Elle est toujours en mouvement. Quand elle est obligée de s’asseoir, ses pieds et ses mains ne cessent de bouger.

Sa recette pour conserver sa taille: Premier déjeuner, de l’eau chaude, avec un soupçon de citron.

Déjeuner, un œuf cuit trois minutes, une rôtie, une tasse de thé sans sucre.

Dîner, un peu de viande.

L’enfant chéri de Nazimova est Salomé. C’est l’œuvre qu’elle a réalisée selon ses idées, avec son propre argent.

« Ce qui rend malheureux les créateurs de l’écran, dit-elle, c’est l’impossibilité matérielle où ils peuvent se trouver d’exprimer ce qu’ils sentent. Un peintre peut réaliser son idéal en mourant de faim dans un grenier: il suffit qu’il ait des couleurs, des pinceaux, une toile. Que peut réaliser un artiste de cinéma, s’il n’a pas une fortune pour tourner un film?

« Aussi j’ai économisé l’argent que j’avais gagné en travaillant pour les autres. Une fois libre, j’ai rapporté cet argent à l’écran qui me les avait fait gagner. »

Ce qu’elle pense du Cinéma

A l’un de nos confrères qui lui demandait, ily a quelques temps ce qu’elle pensait du cinéma, Nazimova répondit:

« J’aime le cinéma. Encore que pour être digne de l’engouement du public il doive être fait de sincérité, comme d’ailleurs tous les autres arts.

« Voyez, je puis exprimer la tristesse, dit-elle en donnant un rictus à son visage; ou la colère — nouvelle grimace. Mais si je n’éprouve pas réellement de semblables sentiments au plus profond de mon être, je ne puis être qu’une quelconque cabotine.

« On doit vivre son personnage si l’on veut que le spectateur prenne intérêt à ce qui lui arrive au cours de l’intrigue. Bien des gens me disent: « Mais, comment pouvez-vous vivre un rôle au cinéma, alors que tant d’interruptions se produisent à chaque instant, que cela vienne des lumières artificielles, de l’appareil de prise de vues, de l’erreur d’un partenaire, d’une sortie intempestive au dehors du « champ »?

Mais, à bien réfléchir, on retrouve d’autres sources de gêne, différentes, mais aussi ennuyeuses, dans les autres domaines, à la scène surtout. Comme dans les autres arts, la sincérité, au cinéma, doit tout primer, je le répète. Je suis sincère devant l’appareil de prise de vues comme je l’ai été devant le trou du souffleur, et j’aime le cinéma tout comme le théâtre.

« En outre, je reconnais avec plaisir qu’au cinéma on peut parfaire tout à loisir son interprétation d’un personnage, tandis qu’à la scène, il n’y a plus revenir sur un jeu de scène, sur une tirade, une fois qu’on les a livrés au publie. Pour ma part, je n’hésite jamais à recommencer toute scène que je sens pouvoir parfaire si peu que ce soit. Evidemment cela entraîne à une consommation de pellicule qui peut paraître excessive, à première vue. Mais au total cela fait tant pour le renom de l’artiste qui se montre si difficile envers son propre travail que la compagnie à laquelle j’appartiens, entre autres ne m’a jamais reproché l’amas de pellicule que je laisse forcément de côté.

« Enfin, déclare Alla Nazimova, s’il est un défaut qu’on puisse reprocher au cinéma, du moins au cinéma actuel, c’est la fausseté, la convention des scénarios. Et, malheureusement, on ne peut réellement vivre son personnage que s’il agit conformément à la vie vraie, que s’il est constamment logique avec lui-même, logique avec la généralité des cas analogues connus. En tout cas, en ce qui me concerne personnellement, je m’estime très heureuse de la qualité des scénarios qu’il m’a été donné, depuis mes débuts à l’écran, de tourner. »

Comment elle tourne

« Rien n’est plus intéressant, racontait, il y a quelque temps Mme Howells, dans La Cinématographie Française, que d’assister à une scène de prise de vue avec Nazimova. Elle entre dans la peau de son personnage avec une conscience, un oubli des contingences extérieures vraiment extraordinaires. Oubliant tout ce qui l’entoure, elle est de toute son âme, de toute sa force à son rôle; aucune gêne, aucun préjugé mesquin, elle vit pendant un moment la vie du personnage qu’elle a décidé de représenter.

« J’ai eu le privilège de lui voir tourner quelques scènes de Hors la Brume et jamais je ne fus impressionnée aussi vivement.

« Nazimova, en fille de gardien du phare, vêtue de haillons et pieds nus, vaque aux soins du ménage; les pirates pénètrent dans la tour qui porte le phare, enferment le père et emportent l’enfant.

La lutte entre la frêle artiste et le rude marin est épique.

« Bien que le cinéma soit muet, Nazimova poussait des cris d’une violence à faire frissonner. Sa voix angoissante pouvait s’entendre à un un mille de là et les assistants sentaient leur sang se glacer. Elle se dégage, le marin la ressaisit de ses grosses mains velues. L’artiste se débat de plus belle; elle mord, elle griffe, elle frappe de toute la force de ses poings et de ses pieds, tant et si bien que le colosse est obligé de lâcher prise.

« L’appareil cesse de tourner; Nazimova demeure sans forces. Puis elle demande au marin: Vous ai-je fait mal? Je crois bien avoir frappé un peu fort…

« L’homme sourit tout en faisant la grimace et montre sur ses rudes bras les traces rouges laissées par les dents de l’artiste, et sur ses jambes de larges taches noires. « Vous êtes très réaliste, madame, dit-il, mais j’ai dû moi-même vous faire mal en vous serrant. »

« Nazimova fait un geste négatif et saute dans son cabinet de toilette achever son sandwich et changer de costume.

« Quelques minutes après elle apparaissait dans une robe merveilleuse d’un tissu châtoyant et constellé de pierreries. En la voyant ainsi éblouissante et radieuse, je ne pouvais me figurer que c’était la même femme qui, tout à l’heure, nous faisait frissonner en petite misérable sans robe et sans souliers…

« Mais c’est le secret de Nazimova d’être tour à tour, et dans la perfection, le ver qui rampe ou le scintillant papillon. »