A. S. C. Member Has Soundproof Booth Built to Prevent Recording Studio Noises.

Du Par adapts Camera for Vocal Reproduction Work; Storage Batteries Used for Lights.

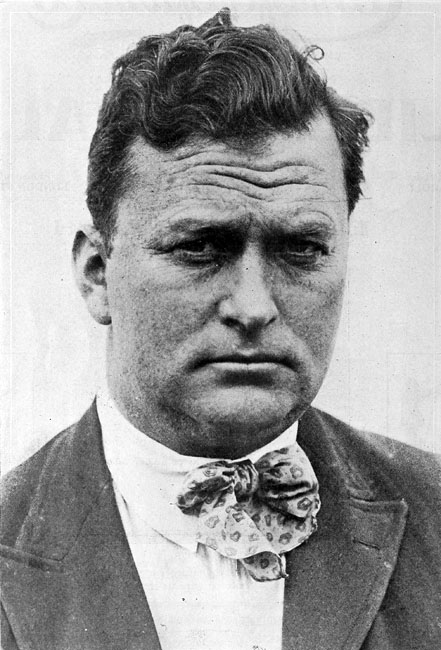

An interesting insight into the cinematographic difficulties which had to be conquered before the new celebrated Vitaphone process, used by Warner Bros, in conjunction with Don Juan, was reduced to the plane of commercial acceptability is shown in an account of the invention by E. B. Du Par. the A. S. C. member who surmounted its photographic barriers and thus made possible the actual application of the device.

Noise Cut Out

“First of all,” Du Par reports, “the noise incident to the taking of a motion picture made it necessary to shut the camera in a special soundproof booth. With the camera, I was locked in the booth. I shot through a small aperture, and looked out through a small peek hole. However, the construction of the booth does not permit of the booth’s occupant to hear anything from without. It is necessary to depend entirely on light signals for starts and fades.

Synchronized

“The camera is run by a motor which is synchronized with the recording machine motor. Instead of running at the regular speed of 16 pictures per second, we exposed at the rate of 24 per second! The recording machine is so located that it is in another part of the building, far enough away so that no sound can get to the actual place of photographing. The apparatus in the recording room is in charge of a recording expert. Another expert is stationed at the ‘mixing panel,’ as we call it, his duties being to listen to what is being recorded and also to watch a very sensitive dial that indicates every little variation of sound. When the dial starts to jump up to a certain mark, he has to vary the amplification on the microphone so as not to cut over certain high notes; high frequencies are apt to make the cutting point on the recorder break through the delicate walls of wax and spoil the record.

Far Removed

“The master recorder,” Du Par continues, “was stationed on the sixth floor above us. He is surrounded by dials whereby he can tell just what the vocal actions of the artists are. He is also attended by a large horn, about five feet square, in which he listens for any foreign noises. The microphones are so sensitive that he can detect if anybody on the set makes the least noise, such as walking, whispering or even the flickering of a light. If such are recorded, then the record is ruined. A flicker of a light sounds out like a pistol shot. This makes for a severe test on the lights. A number runs about ten minutes, or between 900 and 1000 feet. On some sets I have to use big storage batteries, weighing about 400 pounds each; seven of them are required to run a G. E. light of 150 amps. I use batteries to avoid generator noise. On the same lights, we had the gears changed from metal to fiber in order to eliminate gear noise on the automatic feed light.

Adapted Camera

“Since ! beginning this work,” Du Par states, “I have almost remodelled my camera. I use 1000-foot magazines, high-speed shutter, leather belt, special clutches on the take-up spool, and a light signal built right in the camera.

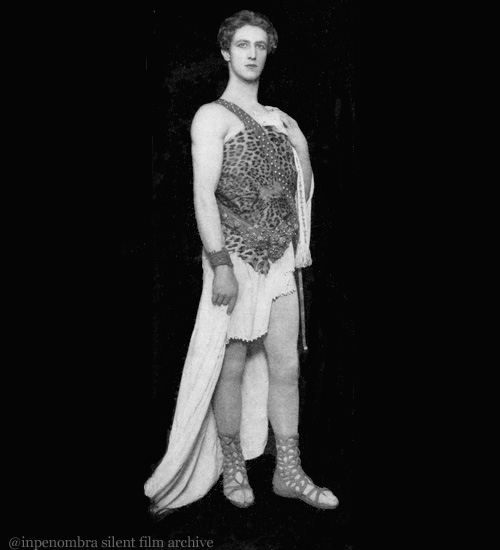

“There is somewhat of a difference in photographing motion picture and then grand opera stars. In the past several weeks I have filmed Mischa Elman, violinist; Efrem Zimbalist, violinist; Harold Bauer, pianist; Giovanni Martinelli, tenor; Marion Talley, and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra of 100 pieces.

“A strange incident occurred when we were taking ‘Swaunee River.’ Everything was still, and I had just received the signal to start; I flashed back the signal that I was fading in and everything was going nicely when I noticed frantic signals to stop. Looking out the peek-hole, I saw that every one was exceedingly excited. The cause, I learned, had been the screams of a colored janitress who claimed that she had seen the late Oscar Hammerstein walking across the balcony. It was eleven

o’clock in the morning, and it is said that it was his old custom to walk across the balcony at that time in the old Manhattan Opera House which we were using to work in. This was the third time that the janitor’s force had claimed seeing Mr. Hammerstein, and of course the commotion ruined that shot.”

(American Cinematographer, September 1926)